The #1 Habit to Help Save the Planet Is As Easy As Eating Vegan Before Dinner

During World War II people in towns across the Midwest turned off their lights and combed the night skies looking for bombers. In cities along the coast, they turned off their lights to not let German boats or subs spot our Navy ships leaving the harbor. These were acts everyone did willingly, to feel part of the war effort, even though the war was "Over There" and had not yet reached our shores–until one day bombs dropped on Pearl Harbor. But even when the war was an ocean away, nightly radio updates made it seem close enough.

The question of climate change is more abstract: How do you get everyone to make acts of collective sacrifice when you can't see the impending danger? This is the challenge of climate change, as posed by Jonathan Safran Foer in his excellent book, We Are Weather Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast, just out in paperback. In his able storytelling, we are treated to feats and facts, both scary and inspiring, about the ability of one individual to make a difference–like lifting a car off a bicyclist to save him–as well as acts of collective cooperation, like moving out of the way of an ambulance in your rearview mirror.

But while some acts just make us feel better, Foer argues, without actually having the actual effect of slowing climate change, other acts make an enormous impact. The one thing everyone can do to have an immediate and significant benefit on the climate crisis, which we all will face but don't see (unless you count pandemics and epic storms and forest fires and rising tides) is to eat less meat and dairy. Emissions from animal agriculture account for one-quarter of the greenhouses gases that humans generate yearly, and that are contributing to the global climate crisis

What makes us feel good versus what actually helps, and how to know the difference

Turning out the lights over small towns across America in June 1944 would have been futile had 156,000 troops not stormed the beaches of Normandy and pushed back the German occupation of France. Safran Foer draws parallels to our current crisis: The war on climate change needs us to not just feel better but do better. What's at stake may not be our own lives, but the future of the planet for our children and their children. Without doing what actually works, all we do is make ourselves feel better. And what works is changing how we eat.

Saving the Planet is a very difficult concept to grasp and hold onto

Saving the planet sounds like a massive task, something Tom Cruise's character would do in War of the Worlds, or The Rock could handle in San Andreas. But what's required is not that type of heroism. We Are the Weather winds together stories and historical events to show us that our job is to win against the current climate crisis, not just to feel better with small acts. Safran Foer tells stories that show individuals who act, like his grandmother who left before the Nazis marched in. In his world, we don't get points for feeling better in the face of the climate crisis. If we do the things that actually make the difference, we get to save our planet for future generations This includes, starts with, and ends with, changing the way we eat.

Foer's stories are honest–such as when he admits that even after writing Eating Animals he still ate the occasional burger–and personal. He tells the story of his grandmother who fled the Nazis, while the rest of her family stayed behind. Why do we as humans feel compelled to act, versus when we can't hold onto those convictions and we fail to act. He uses facts, history, and storytelling to get us to understand not just climate change but to understand human nature.

How did his grandmother know to leave Europe, save herself from certain death or internment in concentration camps, and why did her young sister and family stay behind? She knew she had to do something, he writes. By the time the German soldiers marched into their streets, it would be too late. How could she not convince her sister to come with her? (Instead, she handed Jonathan's grandmother her own shoes to wear.) Why was everyone else in the same situation not as alarmed? Or if they were, then why did they not act, not leave, not save themselves?

Sometimes the danger we can't see is the one we need to pay attention to most

The truth is that weather and climate change are concepts that are "too big" to fathom, or if we can, they are too big to hold onto as we go about our daily lives. We can't always grasp the dangers we can't see, or we would rather not see them. But a collective act of sacrifice is what's needed to win this war, and the danger is lurking, in the form of rising waters, more frequent and disastrous storms, a pandemic and future pandemics to follow. During World War II the questions FDR asked are, Is it a sacrifice if our very lives and freedoms are at stake? Don't think of it as a sacrifice but a decision to live. This is what Safran Foer asks of us now.

So, how can you change something so big that conceptually it's actually hard to fathom it? Jonathan Safran Foer suggests we not leave it to "in the moment" decisions or temptations but that we adopt habits that become rote, so ingrained in our behavior through repetition that we don't even have to think about it. We just become used to acting that way.

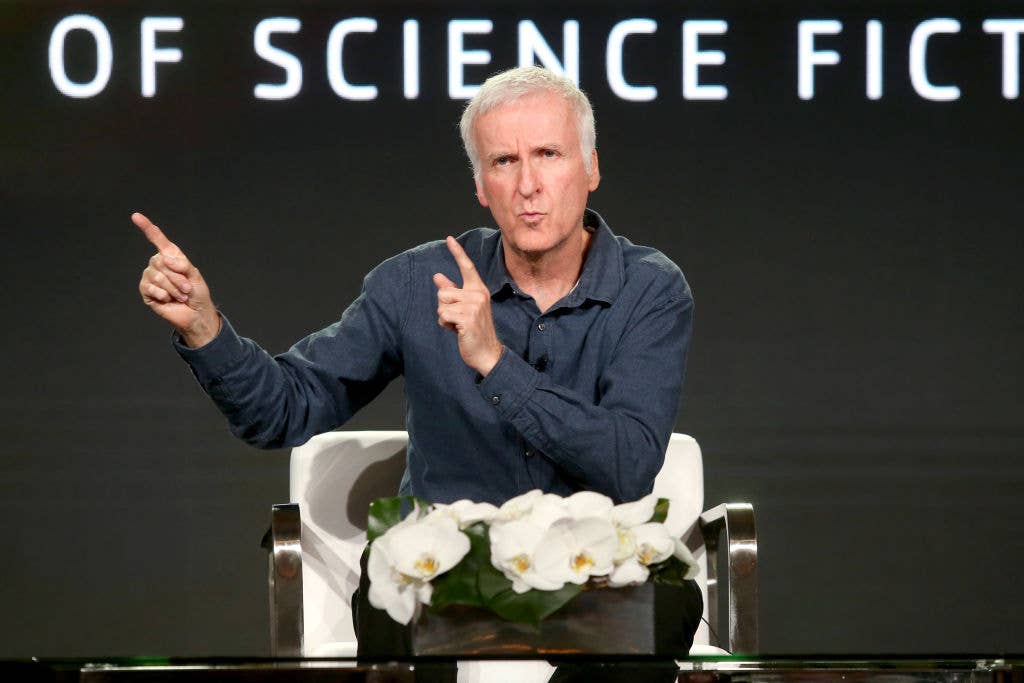

"If we begin creating habits, something you practice so often that you don't even think about it, we can together solve the climate crisis and turn back some of the damage that we have caused. But this is the bare minimum we should do," Safran Foer says.

To help slow climate change and save the planet, eat less animal products

According to Safran Foer, the four highest-impact things an individual can do to tackle the climate crisis are 1. Have fewer children; 2. Live car-free; 3. Avoid air travel; and 4. Eat a plant-based diet. "Most people are not in the process of deciding whether to have a baby. Few drivers can simply decide to stop using their cars. A sizable portion of air travel is unavoidable. But everyone will eat a meal relatively soon and can immediately participate in the reversal of climate change," he wrote in an Op-Ed last fall. "Furthermore, of those four high-impact actions, only plant-based eating immediately addresses methane and nitrous oxide, the most urgently important greenhouse gases."

He adds in an interview with The Beet: "The impact of transportation on global warming comprises about 14 percent of all the emissions that are heating our planet at an alarming rate. Farming, and most of it animal agriculture, accounts for 24 percent." He adds that the number one way to impact your carbon footprint is to eat plant-based before dinner. (This also happens to be a great way to start your plant-based journey toward eating healthier, as Mark Bittman suggests.)

Habit 1 to Save the Planet: Go Mostly Vegan, Eat No Meat or Dairy Before Dinner.

After analyzing food-production systems from every country around the world, the authors of a study published in the journal Nature in 2018 concluded that other than the poorest populations, the average world citizen needs to shift to a plant-based diet in order to prevent catastrophic, irreversible environmental damage. That means, in the US and UK, consuming 90 percent less beef and 60 percent less dairy. The easiest way is to go meatless before dinner.

Habit 2 & 3 to Save the Planet: Cut Down on Transportation by Plane and Car

No one is saying that you end your flights or travel plans. But perhaps instead of flying to see relatives during the holidays, you drive. Or if you can take a bike to town instead of a car, do it. Flying accounts for 12 percent of US emissions from transportation. according to the EPA. Take one less flight, when possible. But know your limits and if not limiting the number of flights you take for work or play, then switch your diet and know you're doing your part, he suggests.

As for car travel, every vehicle on the road produces an estimated 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. if you're going less than a mile for a single item or two at the market, take your bike, or walk, since you can remove a car from the road and help your body feel fitter and get some fresh air. If that's not possible, he suggests you just stick to eating more plants.

"Between transportation and agriculture, eating is the only one of those that immediately addresses nitrous oxide and methane, which are two extremely powerful greenhouses gases," he adds.

Habit 4 to Save the Planet: Limit overpopulation.

We can not imagine future parents weighing the decision to have a baby on the impact it will have on climate change. But Safran Foer suggests that if having a big joyful family and a full dinner table is your happiness, that is your personal choice. And try to eat as plant-based as possible, for the planet, and to the future health of your family.

Every action helps, but some count more than others, and eating plant-based is more important than what you drive, how many kids you have, or how often you choose to fly. "I am not going to judge anyone who buys a Tesla. It just may be that the impact of that is not as essential as we hope it is. I am impressed with people doing whatever they can and not someone to judge. But we have this problem between our emotions and actions and sometimes we confuse the feeling of participation with actual participation. Like people who watch Rachel Maddow and confuse that with action. Voting is action.

"So when we are confronting climate change we have to be honest about what actions matter more than others. And some of the actions we take we do because we like how it makes us feel. They are visible and soothe a feeling of guilt that we have and other choices that we make actually work."

And what works? On this Safran Foer is clear: "What is it that the scientists are saying matters most in terms of the individual's relationship with the environment? It's not ambiguous. It's eating fewer animal products

For many people giving up meat is a tough decision and related to personal identity

Safran Foer explains: "Instead of thinking about it as an identity, think of it as your relationship to your planet, and see it more of a cause-and-effect change.

"The reality is there are very few people in our country or our world who are capable of flipping their identity quickly or if ever. They don't want to, or they have habits that are too engrained, or they simply value the ways they have been and their parents have been and their grandparents have been. This is tied to their habits, culture, and tastes."

The decisions don't need to be binary, says Safran Foer. "If someone said to me, 'You need to stop flying, period.' I would say 'I can't.' Maybe that is hypocritical but I am just not going to do that." Luckily it's not binary. There are shades of gray here:

"If the only option is to do everything or do nothing then we choose to do nothing."

But there are other ways of looking at it. Pretty much every climate scientist agrees that we have to do the best we can, personally. "No scientist says we have to not have more than two children again or never fly again or never drive again or never eat an animal again. There is a huge difference between degrees of moderation."

How does the pandemic affect our views on climate change? Is it making us aware?

"The difference between how people responded to coronavirus as per climate change," Safran Foer says "is that we have been good about mobilizing. And even though the stakes seem to be smaller, but the answer is that we have a selfish desire to be healthy. People wear masks and social distance in large part because they don't want to get the virus.

"With climate change by the time it gets personal, it will be too late to solve."

This is hard to keep front of mind, even in a pandemic, Safran Foer admits. "I clearly believe in climate science and I don't doubt for a second that humans are to blame for climate change, and the stakes are high, and yet I have been having a hard time doing what is necessary to do the right thing. The answer is that we have to change our social norms."

What do you say to the person who wants the burger?

Safran Foer explains this makes you human: "I say: 'That doesn't make you bad or weak, and if you have a burger once in a while the world is not going to fall apart. But let's not overstate or understate the power of the individual and let's be honest about who we are and how difficult it is to overcome primitive cravings.' And let's be honest about the science and the relationship. We really know the relationship between food and the climate: We have to eat less meat. It's not just an opinion. It's not a statement about animal welfare and any other problems with the meat industry. It's simply science.

We have to eat less meat to solve this problem of climate change.

The most comprehensive study was published at the end of 2018 in Nature. Scientists found that while there are certain areas that are malnourished, and those people could afford to eat a little more animal product. But for citizens of Europe and the US the UK, who do not have a problem with malnutrition, we need about 90 percent meat and 60 percent dairy to avoid what they call catastrophic climate change.

We are eating vastly more meat than we used too. Vastly more. Factory farm which didn't even exist 75 years ago and only started to come into real prominence about 40 to 50 years ago. A traditional American meal was not a plate 2/3 of which is covered with animal protein. There would be grains and vegetables and starches but not as much meat.

So how do we do better every day? By habit. You go into a store and you don't shoplift. You shop. That's a habit. It's what you do because you don't steal. We have to transform ourselves into people who don't steal from the planet and steal from the future. Big thoughts are not going to get us there. Habits are, specifically the habit that you tell yourself: I don't eat meat before dinner.

To avoid another pandemic, going plant-based is part of the solution, Safran Foer says:

"This is another reason that we have to care about these decisions. The CDC has said that 3 out of 4 new and emerging contagious diseases have developed on factory farms. There is a direct line between the way we treat the planet and the way we grow food and the prevalence of epidemics.

"As horrible as the novel coronavirus has been, we will have gotten relatively lucky if the mortality is .05 since, with the bird flu, it was 60 percent of those who got it, and 50 percent of the kids who got it died. Imagine if 50 percent of kids who got coronavirus today died. And there is no reason in the world when we are not going to be hit with another one of those diseases when we are creating the perfect conditions on farms.

"Our farms have become Petri dishes for diseases, and like coronaviruses, the bird flu does not care about national boundaries. It will develop anywhere and move from Brazil to China to America, and it doesn't care about species either. It will leap from birds to animals to humans. That is what happened here. The reason it is called 'novel' coronavirus is that we had not seen this is people before. It had been in animals before.

As for what's next for Safran Foer, he is turning his attention to fiction. When asked if he would consider writing a novel focused on this type of pandemic scenario, his chilling answer was: "It's hard to imagine a novel that would be able to capture how horrific this situation is."

More From The Beet