“Bee Keepers Love Bees.” A Beekeeper Sets the Record Straight About Honey

The topic of honey can be one that engenders debate among vegans and bee-lovers from all over. While vegans don't partake in eating honey, many who consider their diet plant-based do. When choosing honey, how do you find one that is pure, created by happy bees, and that is extracted in a way that is the least harmful to the bees that we all love and admire?

When we set out to find the answer to those questions, we researched the different processes used by beekeepers so that honey lovers could be educated consumers. After all, honey is both a natural sweetener and is considered by some to be medicinal, with anti-bacterial properties that rival medicine when it comes to treating cold and flu, sore throat, sinus infections, and even seasonal allergies. But we don't want to enjoy honey at the expense of the beloved bees, which are natural wonders of organization and hierarchy and which have been enjoying a much-needed resurgence during the pandemic, one of the few silver linings.

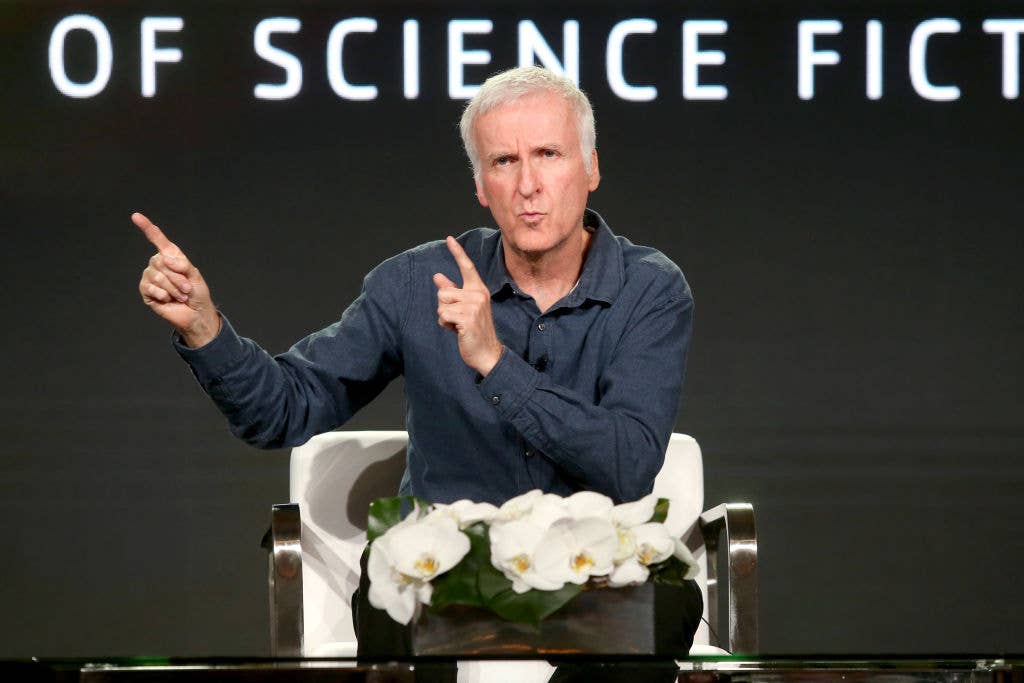

So when The Beet wrote about how to choose honey that was the least harmful to bees, we heard from a beekeeper who took issue with several aspects of the story. Eager to get it right, we interviewed Chris Theiler, the beekeeper in Summertown, Tennessee, who has about 50 hives (it's not his day job) and a wealth of information about how beekeepers do their jobs with the bees that they love and work with.

First and Foremost, Beekeepers Love Bees

"Beekeepers do not want to hurt bees," says Theiler. "When you take the honey in a way that is responsible, you're not hurting any bees." His main point is to find honey from a beekeeper that is responsible. "There are a lot of misconceptions out there about harvesting honey, No bees are being hurt when extracting honey."

"The perception is that harvesting honey destroys hives. Yes, in some instances you are cutting wax from a wooden bar and crushing the wax to get the honey. But first, you get the bees out of there. The honeycomb is not the same as the entire hive. How you get the bees out is up to you," he explains.

"You can do that a few ways: You can take a brush and brush the bees off the honeycomb and the bees will go back into the hive. I use something called an escape boards. The bees can go down through the board and not go back up to where the honey is."

"No bees are in the honeycomb once they go out the escape board. They go back into the hive they are oriented to. So this whole perception that there are bees getting hurt when you harvest the honey is wrong."

"Now, that is the case in the U.S. I can't attest to what happens overseas. In the U.S, we gently remove the bees from the honeycomb, and then we use a centrifuge to spin the comb and it extracts the honey from the comb. None of the bees are hurt. I have a video of the centrifuge."

For most people, keeping bees is a passion

"I still have a day job. But I have about 50 hives. When you are looking at honey production, the general average for a mature hive in my area is 60 to 100 pounds of honey per hive every year. That is variable, depending on the year, the weather, and management, but that is it.

"Some hives have made almost no honey this year ... So then you have to help the bees along. You feed them sugar syrup [for food]. But then you do not harvest honey from those hives. If you have fed the bees, what they produce is not honey The bees end up with a honey-like substance in there, but it's not actually honey, since it's not from nectar. If you feed a colony sugar it does not become honey. So you never pull honey from the hives that you've had to feed.

"Everyone loves the idea of "organic" but that can be a bogus label when it comes to honey since there is virtually no way to know where the bees are getting their nectar. Bees fly 3 to 5 miles and bring nectar back, so "organic" is a farse when it comes to honey unless you test a single batch. Other than that, you can not get a blanket certification when you have bees flying all over.

How Do You Know What is In the Honey You Buy? Or that It's Real?

"Honey is the third most counterfeit product on the shelves. At a recent world honey conference in Montreal, they used Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to measure the molecular structure of all the honey that was submitted to judges and said 45 percent of the honey was contaminated or adulterated, and they only had about 50 percent that they could judge as actual honey. It's common for honey imported from other countries to be cut with brown rice syrup because it's cheaper. This mostly happens with Asian exported honey."

So where should we, the general public buy honey that we can trust?

"You can know your beekeeper and trust your beekeeper, or do it yourself. If you don't want to raise them yourself, simply buy domestic honey, preferably local and only honey that you know where it's coming from. Ask a local beekeeper for a tour of their apiary, most love showing off their hives.”

"Looking for the words "Pure Honey" on the label is nearly meaningless. The US government has done a terrible job of prosecuting false food sources. Even here in Eastern Tennessee, there is a case where a company is selling “local honey” that is suspected of using imported honey from Vietnam, mixed with pollen from Tennessee. They sell it 3 to 4 dollars a quart wholesale --which tells me that it can't be pure honey. Big companies can buy overseas honey that has been adulterated and then marks it up and sell it as local for much more and their profit margins are huge. Lawmakers should be working on federal law to prevent this."

So the bottom line is…

"Buyer beware. If you can meet a local farmer or beekeeper you will be able to know and trust that the honey is real... Go on social media and you can find local beekeepers sharing bee-related content. You can even learn to keep bees for yourself. There are a ton of people who do it on the roofs of buildings in New York City. There is even a division of the NYPD that has to come in when there is a swarm, and they have to remove the bees. A couple of years ago a swarm landed on a hot dog cart in Times Square and they had to remove it, which got national attention -- and set up a new hive off-premises. So even in New York City, they know the importance of honeybees."

If you see a swarm, what should you do?

"Call a beekeeper and most will remove it off of a branch or bush for free. If it is inside a wall, and I have to cut a wall open, then I will charge for it. But for me, or other beekeepers, catching a swarm on a bush is maybe an hour of my time... A swarm can be up to 30,000 bees but generally, they are well fed and won't sting you, they are just looking for a new home."

"If you see a swarm, it's a hive that has grown too large, typically because they are healthy. And they will raise a new queen and the old queen will look for a new home. They have no brood or food to defend, so they are generally the most docile ever. they will fly to a new location and they will immediately start building a comb. They have to be full of honey when they leave their old hive, in order to start drawing wax immediately. A new swarm is full and a full bee is a happy bee. I walked up to a swarm last year with my daughter who is 9 and the kids next door that are 8 and 6 and 3. And all the kids sat 15 feet away from it and I started scooping the bees with my bare hands and they did not hurt any of us. That gives you an idea of how docile a swarm of bees can be."

So what you want the public to know is…

"Beekeepers are not hurting bees intentionally when they are harvesting honey. Almost everyone is doing it the same way I am doing it, although some are on a much larger scale. So it is helpful to clear this up: Harvesting honey does not hurt any bees. We love bees."

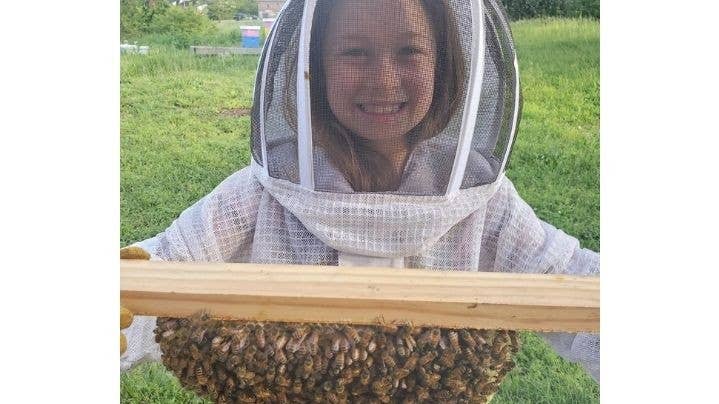

So for me, as luck would have it, my local beekeeper who has an organic farm just down the road from my house, is actress, model, filmmaker, and bee-lover Isabella Rossellini, pictured here tending to her bees in Brookhaven, Long Island. I am heading there for some honey as soon as I finish this story.

For local honey, get ahold of your local beekeepers association and get the list of contacts that have local honey available for sale. If you're in the Long Island area, check out this resource to find your local beekeeper.

If you are interested in learning about raising your own bees, hosting hives on your property, and even honey-making for yourself, a helpful resource to start with is Bonac Bees.

More From The Beet