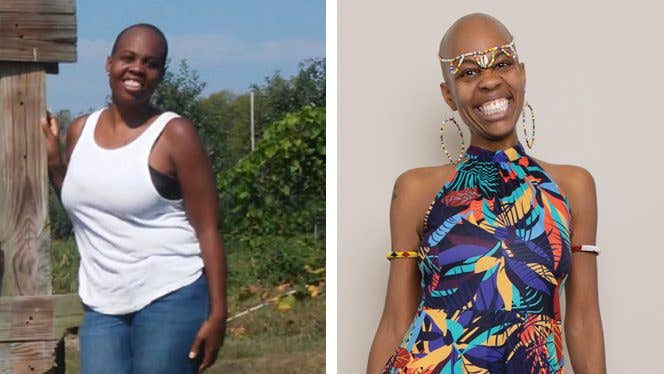

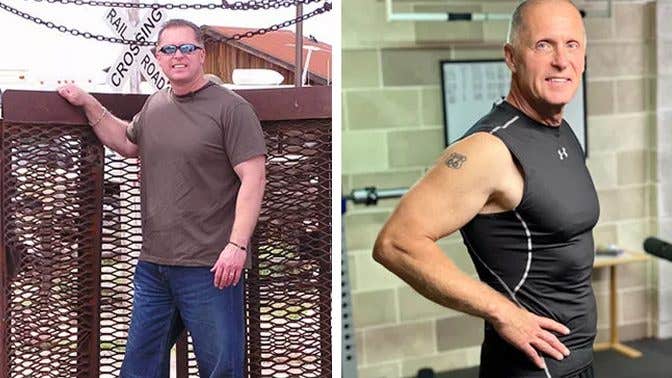

EMPOWERING PEOPLE TO LIVE HEALTHIER LIVES THROUGH WHOLE-FOOD, PLANT-BASED NUTRITION

Huge Savings This Memorial Day!

Get our lowest price ever on the Forks Meal Planner. Save 50% on all annual memberships. Thousands of easy plant-based recipes right at your fingertips and so much more.

TRENDING NOW ON FORKS OVER KNIVES

BROWSE MORE RECIPES

All RecipesAmazing Grains RecipesForks Flex RecipesLunches and DinnersSidesVegan Baked & Stuffed RecipesVegan Breakfast RecipesVegan Burgers & Wrap RecipesVegan Dessert RecipesVegan Menus & CollectionsVegan Noodles & Pasta RecipesVegan Salads & Side Dish RecipesVegan Sauces & Condiment RecipesVegan Snacks & Appetizer RecipesVegan Soups & Stew Recipes

Join our mailing list

Get delicious recipes, expert health advice, culinary tips and special offers from Forks Over Knives and our curated partners.

By providing your email address, you consent to receive newsletter emails from Forks Over Knives. We value your privacy and will keep your email address safe. You may unsubscribe from our emails at any time.